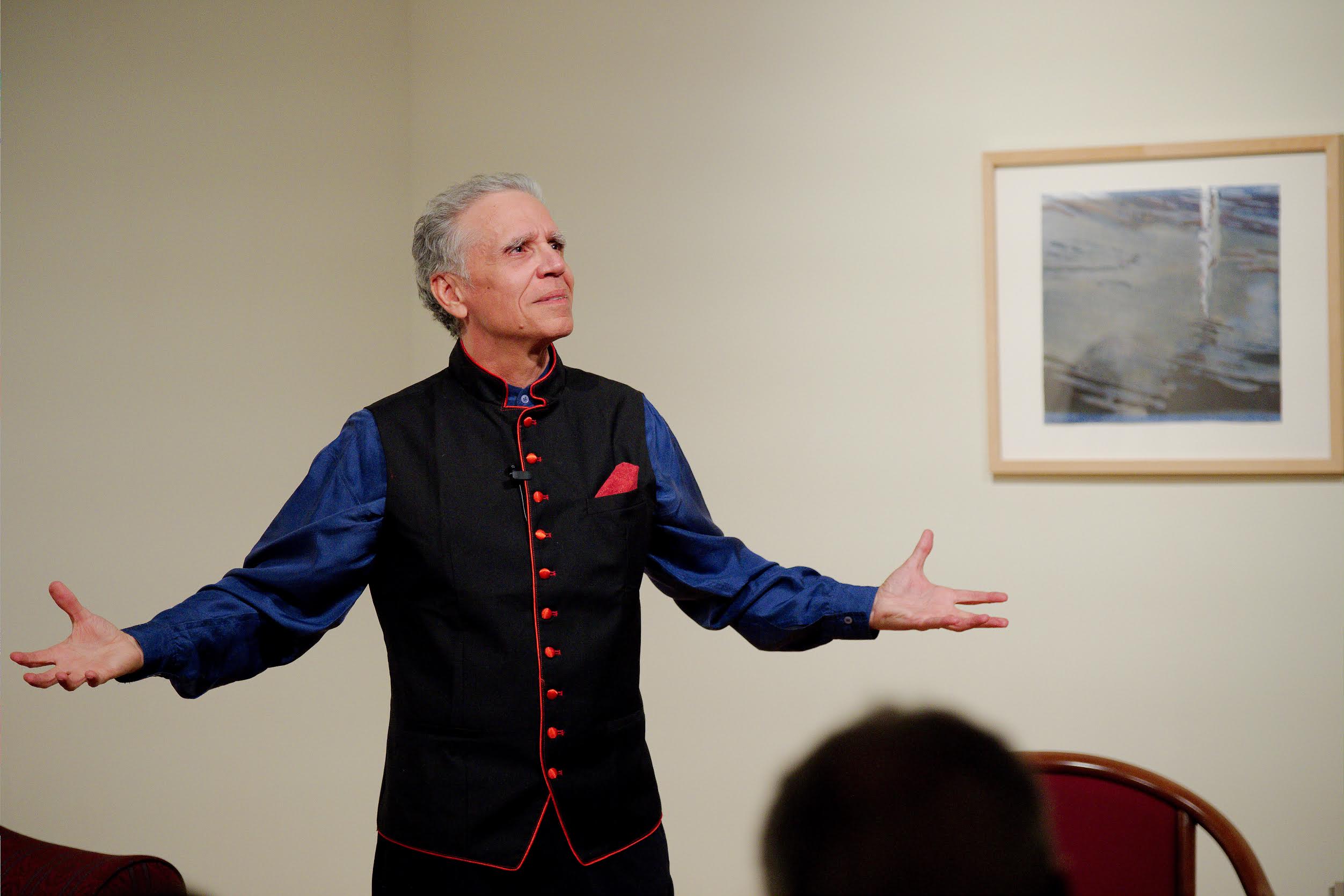

Professor González believes that poetry is meant to be spoken out loud, not just read on paper.

by Dr. Robert González

Associate Professor of Speech and Theatre

To save our sanity, and even our souls, swirling distractedly within today’s mad hurly-burly – its raucous, crass cacophony of ubiquitous advertising exhortations, continuous digital connectivity, and bombastic political bear-baiting – we need to revive and popularize the ancient art of the rhapsode.

In ancient Greece, rhapsodes performed the poetry of Homer and Hesiod, classics held sacred in that society. Rhapsodes were “song-stitchers,” in that they would “stitch” together passages from these longer epics, adding their own words between them.

Rhapsodes rhapsodize by performing rhapsodies. Most people now define those two terms, respectively, as wild enthusiasm and an eclectically structured piece of music. These meanings derive from the ancient Greek rhapsodes’ practice of creating dramatically charged performances from a diverse collection of passages from the work of their revered national poets. Both the rhapsode and the actor came into being around the same time in Greek history – the advent of literacy. Previously, when Greece was an oral culture, poets sang their songs from memory, stock phrases, and improvisation. With the increasing use of the alphabet, rhapsodes evolved from using scripts as memory prompts for extempore performances to memorizing texts to perform verbatim. Then, over the centuries, with the spread of writing and literacy, and especially with the invention of the printing press, the communal performances of rhapsodes eventually were replaced by silent, solitary reading.

Consequently, the voice of great poetry began to die. Thankfully, the arts of the theatre and oratory preserved the widespread opportunity for hearing beautiful, shapely language – preserved also in writing but designed to be heard rather than read silently. But just as the song of epic poetry gave way to the written prose novel, so lyric poetry surrendered its voice to inked lines on paper. To right this wrong, particularly in this present age, the rhapsode needs to return to grace contemporary audiences.

Poems need to be approached, not as written lines only to be silently read, but as musical and dramatic scores, both of which are “blueprints” for performers. Just as works of music and theatre are not meant to be silently read by their intended audiences, but performed by intelligent and skilled interpreters, so also many great literary poems are meant to be performed. As poets and teachers of poetry agree, poems better approach their potential as musical, emotional, and intellectual texts of influence when they are spoken aloud. They best approach that potential and greater connection with audiences when they are performed dramatically, with full attention to – and best realization of – the music, imagery, story, drama, argument, senses, and emotions contained therein. Actors with the skills and sensitivity to perform the plays of Shakespeare and other verse playwrights seem the most logical choice to lead what we might call this Rhapsode Renaissance, although others who would perform classic poetry dramatically may follow.

Contemporary rhapsodes, as I see them, perform the classic poetry of their language and culture, poetry that has stood the test of time, whose lines speak both a universal and unique message to the hearer, that holds a status within the culture similar to that held by Homer’s in ancient Greece. Poetry dating from the sixteenth century into the early part of the twentieth century now lives copyright-free and easily available as performance material for actors skilled in performing verse (the lion’s share of Shakespeare’s plays).

As it is necessary for classical production companies to make the plays of Shakespeare and other classic playwrights intelligible, relevant, and exciting to contemporary theatre audiences, so it is vital for rhapsodes to do the same for classic poetry. Present day audiences, though in dire need of the intensely humanizing gifts that classic poems bear, are often blocked from entering into the beauty and wisdom of those poems because they live in an era far removed historically and culturally from that in which the poetry originated. They likewise are impeded from deciphering the enigmas of classic poetry because of its archaic vocabulary (thee, thy, thou, ere, betimes, etc.), inverted syntax (“A damsel with a dulcimer/In a vision once I saw”), dense use of figurative language (metaphor, simile, metonymy, etc.) and highly structured metric patterns (iambic pentameter, trochaic tetrameter, etc.). It is then the duty of rhapsodes – by performing this vintage verse with intelligence, understanding, and technical skill – to bridge those gaps of history, culture, vocabulary, and figurative language in their performances. By doing so, they can succeed in vastly enriching the lives, and perhaps saving the sanity and souls, of their audiences through the wealth of their poetic heritage.

Leave a Reply